Visual arts and the beauty they represent are justifiably hailed as one of mankind’s most remarkable feats. In a world plagued by conflicts and disasters, the aesthetic embodied by magnificent works of art is proof that the human spirit prevails and even triumphs over darkness.

We turn to paintings for a respite from suffering. When we see Adam’s hand reaching for God’s extended finger in Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam,” what we are really looking at is a representation of divinity, a reminder of man-made magic.

But for Israeli artist Lihi Turjeman, art – and especially her own unique and complex process of producing it – is more often than not very far from glorious enlightenment. If anything it is a tormenting journey. In her studio, Turjeman dives into excruciating physical labor, whose end result is her enormous paintings in which she dissects, breaks apart and rebuilds her own visual interpretations of themes such as identity, belonging, geopolitics and the notion of home.

Her method of work, which the painter refers to as “action painting,” is a grueling dance with the canvas. She uses an assortment of different materials and colors and imprints them on the cloth through her main tool: Turjeman’s own body. Pressing, kneading, chafing, stomping on and even burning the substances she works with, the artist instinctively carries out a series of actions to excavate new and unexpected forms. If other painters are masters of their own technique and deliverers of beauty, then Turjeman is somewhat of a coal miner, blindly digging in the dark in search of gold.

“I feel like my body is a site, because I work with it. I love working this way, but I don’t want it to ruin my life. It’s hard to explain the insane duality between the body as an art-making machine and your own private body,” she shares.

The artist says that she doesn’t have ultimate authority over the materials she employs. “They spread, they move, they surprise me, they cause reactions. I was always interested in working with large dimensions because of the possibility to lose control while working, to relinquish control to begin with.”

Lihi Turjeman, Walls Layers on Canvas, 2013

What does the process look like if it’s completely out of her hands? “I am not painting a picture that I know in advance. I create more and more actions, and charge my canvas from the very inception of it to the final moment. That is the infinity of painting: There are so many possibilities in the canvas and in its meeting point with other materials and with the body’s movements. I often create a surface underneath the canvas, so that it will show up later and affect it.”

The painter admits that this style of creating is “really exhausting, and often frustrating. Not always, sometimes I have a lucky day and then my movements are lighter than the wind. My body is light, and there is lightness in my relationship with the canvas. But there are days when I don’t know my way. And then, to choose to work on such days is like deciding to go climbing a mountain on a foggy day. It’s a risk. You can climb and bad weather could hit or you could lose your strength. And then the work is really about how I will emerge from it.”

No clear boundaries

Turjeman’s wild exploration is also characteristic of the subjects she corresponds with in her monumental, attention-grabbing works. In one of her recent exhibitions, 2016’s “Center of Gravity” that was showcased at Sommer Gallery in Tel Aviv, she tackled the explosive topic of borders. Addressing iconic sites in Israel such as Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, Turjeman harnessed the status of these places to create a detailed and enigmatic topography she displayed in paintings that questioned the idea that there is one starting point from which we all set out.

Lihi Turjeman, Center of Gravity, 2016

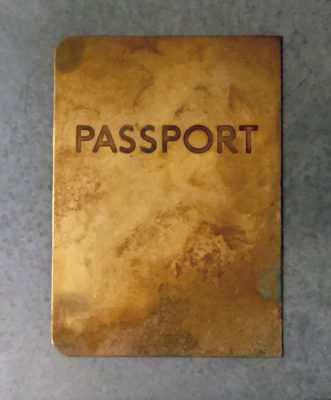

Works like a steel plaque engraved with the word ‘Passport’ in the same font regularly used by border control authorities seemed like an invitation to join the artist on her uncertain journey, for which a destination is not yet defined.

“The question of borders will always preoccupy people, and artists in particular. Our entire infrastructure as a society is founded on borders,” Turjeman explains. “Personally, I always had a problem with borders, with boundaries. I never had clear boundaries between myself and others, or the places where I had been. It was very symbiotic and my art fed from this symbiosis,” she recollects. “There is no guidebook in life that tells you: ‘Okay, here is where you draw the line.’ But I improved, and I have learned to develop boundaries.”

Lihi Turjeman, Passport, 2016

I share with her that one of the paintings from the exhibition caught my attention in particular and lingered with me for years later. Titled aptly “Welcome Back Traitor,” it alludes to the biblical scene in which Moses stands atop Mount Nebo. There, the man who ushered the Israelites through the desert for 40 years get a heart-wrenching glance at the Promised Land he will not live to enter. Turjeman cast her searching glance on the strange scene, charging it with her own longing. It spoke volumes of the woes of immigration, of the agony of those who are fated to always stand at a slight remove from things and narrate the ending before the story even begins.

Turjeman concurs with my assessment. “I am interested in mythological, archaic moments of looking from afar at something that you yearn for and want to reach. It stems from a personal place, a longing for something elusive,” she reflects.

The artist says that while she may not be in the same headspace as the one in which she crafted that piece, the internal voice calling on her to wander has persisted – so much so that it sent her away from Israel to Italy, where she relocated and currently lives and creates.

“I’m renting a studio in Turin, where I live. I would never have chosen to live there,” she reveals with a laugh. “But I did a residency in Italy not far from Turin a few years ago, and I let myself become a guest of Italy. I dove into a new place with a culture, stories and language I didn’t know and it made me fall in love. And then I fell in love with a man there, so I stayed. It was a journey in quest of love. Some journeys you set out on and you prevent yourself from getting attached or staying because you know you have to go back home. This trip was not defined for me as a trip with an end date, I set out in search for an opportunity.”

Everyday life is not as prosaic as the imagery she crafts. “I go to the studio every day and I try to reinvent everything, I start from zero every single day. And there is a contradiction here: I am full of history, other histories dictate my own, and yet I keep trying to start from scratch.”

Lihi Turjeman

The power of the written word

Unlike many other artists, visual stimulation doesn’t drive Turjeman’s work. Instead, she turns to the written word to gain clarity. “I always write before painting, I hardly ever make sketches. I write what goes on in my consciousness as a painter,” she says.

“Sometimes I even plant little text in my works, and because they’re so big people hardly ever notice. I don’t do it often, not enough, probably because the relations between the written word and painting are not entirely clear,” the painter adds.

Her manner of writing, in a mix of Hebrew and English, is somewhat chaotic. “There are endless notes, endless notebooks. There is no logic or order to it, my cursive is hurried and ugly. Sometimes I can’t paint, I can only write. The paintings don’t come to me, I get frustrated, but at least I am writing. But I never ever read a word of anything I wrote. I’m embarrassed.”

Lihi Turjeman, Have, 2018

One such text that snuck into her work is at the center of a floor painting the artist showcased a few months ago in a group exhibition at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem. Created in Italy two years ago, the painting displays in big, block letters the word “Have” – which means ‘Welcome’ in an ancient Latin dialect. “I came upon this word during a trip I did in Italy,” Turjeman remembers. “I went to Pompei, which is such an obvious tourist attraction, but for me going there was like reaching my own private gold mine. I traveled around the destroyed houses and found this text. I looked at this lame mosaic and thought about entering home, how people place doormats at the entrance to their house.”

Turjeman jokes that the work, which she had presented both in Italy and in Israel, evoked mostly confused reactions. “I’m trying to explain what this word means, what my work means. When people don’t understand me I don’t regret it, because that’s exactly what I love doing.”

Discover & Collect Lihi Turjeman’s works here.

Joy Bernard is a senior news editor at Israel’s leading English-language daily Haaretz. Based in Tel Aviv, she writes about politics, arts and culture in the Middle East for various publications.