A woman clad in a sizzling-red one piece swimsuit reclining on her elbows, bare legs casually bent, is seen resting on a black-and-white surface whose repetitive patterns bring to mind decorative rugs or the pristine, cold tiles one would expect to find among the folds of interior decor magazines. The lady in question is unavailable to the onlooker; her face is turned away, gaze invisible, offering no recognizable features. Her cloud of black hair merges with the monochromatic backdrop she is perched on.

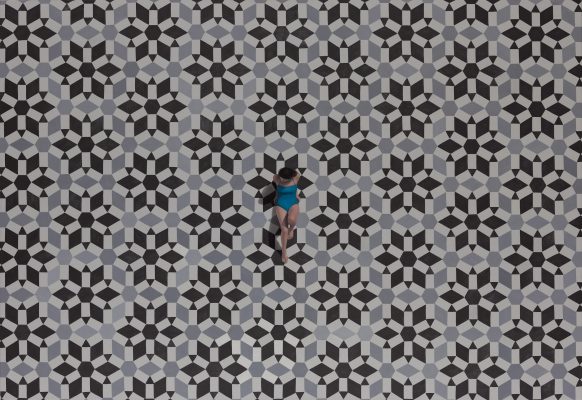

A different frame shows the mysterious character from a farther perspective. This time she is depicted wearing a blue, pin-up bathing suit in the same style, suggestive of another era. The second painting offers a snippet of intimacy: The lightest trace of a dark brushstroke adds delicate eyelids, showing the viewer a lady whose eyes are gently shut. Perhaps she is nodding off in the sun, or daydreaming.

Maya Gold, Marrakech, 2017

Yet another image provides a glimpse of the long-legged femme fatale through a higher, more distant viewpoint. She seems lost in thought, unaware of the painter who created her or the viewer now eagerly leaning forward in an attempt to size up more information, understand where and when these hyper-realistic images – all titled Marrakech, 2017– were crafted or what story they are quietly telling. This woman is a clever nod to the history of art: The iconic female bather, and her nude or sometimes revealingly dressed figure, have graced the canvases of many masters – from Cézanne to Matisse and Picasso. At the same time, the Marrakech bather is disconnected from the echoes of classic traditions; she references no one and belongs to no one. She is all her own.

Maya Gold, Marrakech, 2017

The same can be easily said of her maker: Israeli painter Maya Gold, a respected name in the local art scene, refuses to be beholden to one artistic movement or style. In her 15 years of work, her paintings have taken on myriad themes and color schemes. Each new body of work she springs forth with is a new experiment, breaking with past practices and trademark techniques.

Gold, a graduate of Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of the Arts and a lecturer there, has exhibited her works both in Israel and internationally. She lives in Tel Aviv and creates there as well as in Brussels, Belgium.

I arrive in her studio on a rainy day. In the few hours we speak the deluge stops momentarily and the sun reemerges, caressing the large and white room and filling it with light. Trying to decode the enigma behind her artistic fingerprint, I tell the artist that paintings like the Marrakesch series seem to me like peculiar notes from an unidentified place, postcards from nowhere. “They really are postcards I send from nowhere,” she enthuses. “In terms of technique, size and medium my works differ from one another. In my last exhibition I painted with oil on wood, prior to that I usually painted with oil colors on canvas. Now I am suddenly embroidering. So even in terms of material there is nothing that unites my works. One thing that does connect them is that there is never a clear location. I never drew places,” she reflects.

How does she explain her aversion to pinning her works to one specific point? “It’s connected to my lack of orientation in space. It’s like I have some dyslexia related to geography,” Gold admits with a laugh. “It’s also because I was never interested in the horizon in the painting, or in landscape painting. The classical perception of painting as a window to reality doesn’t attract me to the medium. Instead, the idea of corresponding with someone, having an addressee, is very present in my works. But there is not one place I am corresponding from.”

Maya Gold, Lily, 2018

A bird’s eye view

Gold may fleet excitedly between the different ideas that capture her attention, but one element almost always accompanies her craft: A heightened and faraway perspective. At once frighteningly realistic and dreamy, her paintings unfurl scenes that make themselves known slowly and often require a second and third glance until their vague elements merge into one poignant story.

Gold’s characters occupy intangible places and their actions are bizarrely mundane: Raking leaves or clutching umbrellas against a painstakingly accurate asphalt backdrop, they appear like life signals the artist is sending from the distance. “The distance I put you in, as the viewer, is significant. It’s not a painting that invites you in or asks you to follow a certain gesture of mine,” she admits. “They offer a perspective from afar. Maybe from the world beyond… it’s not really a bird’s eye view, it’s the viewpoint of a ghost, a person with wisdom, someone who is not necessarily alive. Maybe me in the future,” Gold reflects.

When told that this practice can be intimidating and slightly alienating for the viewer, she muses that her paintings “allow the spectators to be super-viewers. They become part of what happens in the painting but they are also outside of it. I think that is related to my relationship with the world.”

Maya Gold, Untitled, 2019

Sisyphic effort

When we glance around us at the nearly-finished artworks leaning against the walls, they look nothing like what I have come to recognize as her familiar outlines. For her current exhibition, titled “Threads”, Gold briefly abandoned her usual practice for a new medium: Embroidery. The novel artworks, carefully and slowly hand-crafted by her on enormous white canvases, feature large and elegant flowers. “This is by far the weirdest thing I’ve done to date, it was completely unexpected for me,” she reveals smilingly. “The circumstances of how I got into it are funny,” the artist shares. “I needed to hang a curtain in my apartment because the light was too strong there, but I couldn’t find a handyman who would do it for me. I’m so clumsy, I can’t work with my hands when it isn’t painting. But I ended up buying a thread and a needle and started sewing. Suddenly I really enjoyed the action, and it was a little like when I first started painting. I had no idea.”

The fresh start felt liberating, Gold says. “That’s how I approached embroidery. I didn’t care about the history of the practice or how it’s done today. I don’t correspond with anything and anyone, ever. It was burning in me, so I took a piece of paper and started embroidering on top of it. At first there was nothing, I just embroidered some leaves. Within a few days I tried it on canvas, and because I am a painter I drew skies and embroidered on top of it. It was a very naive development, until it reached a point where I understood what I was doing. I always understand what I’m doing only as I’m doing it. It’s a lot of hard work and failures.”

Despite the pleasure she derived from foraging into an uncharted territory, the painter says she believes this was her last time working with thread and needle. “These works are instead of painting. They expose the process, every little pixel, they reveal the methodology. It was a very meticulous and sisyphic effort.”

When I express surprise at the fact that she ventured into this unknown manner of work, Gold responds that “for those who don’t see the process behind it, it may seem strange that I embroidered. But this is a result of four years of work, of experiences of a person who has changed. It’s a process.”

Maya Gold, December, 2019

My dear painting

Indeed, gradual change is an important aspect of Gold’s work. While her paintings may look tauntingly aesthetic, they are often a result of pained labor and a lot of frustration. One avid example is the work “Forest in the Rain,” which she rushes to show me. Placing it in her lap, she says: “What I’m showing you now is the final result, but I can’t begin to tell you how many failed attempts are behind it. I threw about 50 of them in the trash with immense relief.” The intricate geometric painting, which shows drops of rain landing between dense rows of cypress trees, was for Gold an exercise in perseverance.

Maya Gold, Forest in the Rain, 2016

“It was very important for me that there would be no perspective or horizon in the painting, for it to appear uniform. It was interesting for me to explore how I can bring the backdrop to the foreground of the painting, how to take something that is usually the ultimate backdrop for a painting – the sky – and turn it into the main thing. It was frustrating. People who visited me in the studio in those weeks couldn’t get what I was talking about, no one saw neither drops nor a forest.”

Eventually, Gold inserted the image of a deer into one of her sketches. “I decided to make it its own painting, and called it ‘My Deer Painting,’ with an obvious play on words. It was the most realistic painting I had ever made. It completed the vision for me. When people walked into the exhibition, I can’t tell you that all of them understood they were seeing a forest in the rain. But for me it was finally clear. And it is one of the works I love the most, it was so difficult to make.”

Maya Gold, My Deer Painting, 2013

If crafting artwork is so challenging, why does she keep doing it? “It’s fascinating and hard, but I believe in hard work. I’ve been in the studio for 15 years, but because I work so intensely it sometimes feels like 40 years years. In order to make a painting you sometimes have to stoop very low. And yet it makes me so happy.”

As I turn to leave the rain pelts the windows of the studio. Gold suggests that I stay until it abates. We sit together for a few more moments, sifting through images of paintings she created with oil on wood that appear like stained-glass windows. As she explains the technique she applied to create them, I think that they, too, seem like images that could appear on the back of a postcard. She points at one of them, a green parrot, and says she named it Lulu “after a parrot in a story by Flaubert about a woman who loses everything she has, and eventually loses her beloved parrot too. To me, the window I drew looks out into what this woman imagines or thinks. But we can’t really know.”

Discover & Collect Maya Gold’s works here.

Joy Bernard is a senior news editor at Israel’s leading English-language daily Haaretz. Based in Tel Aviv, she writes about politics, arts and culture in the Middle East for various publications.