In one of the most inarguably epic children’s books ever written, French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry had put the following words in the mouth of his otherworldly, strangely optimistic protagonist, the little prince: “All men have stars, but they are not the same things for different people. For some, who are travelers, the stars are guides. For others they are no more than little lights in the sky. For others, who are scholars, they are problems. But all these stars are silent. You – you alone will have stars as no one else has them.”

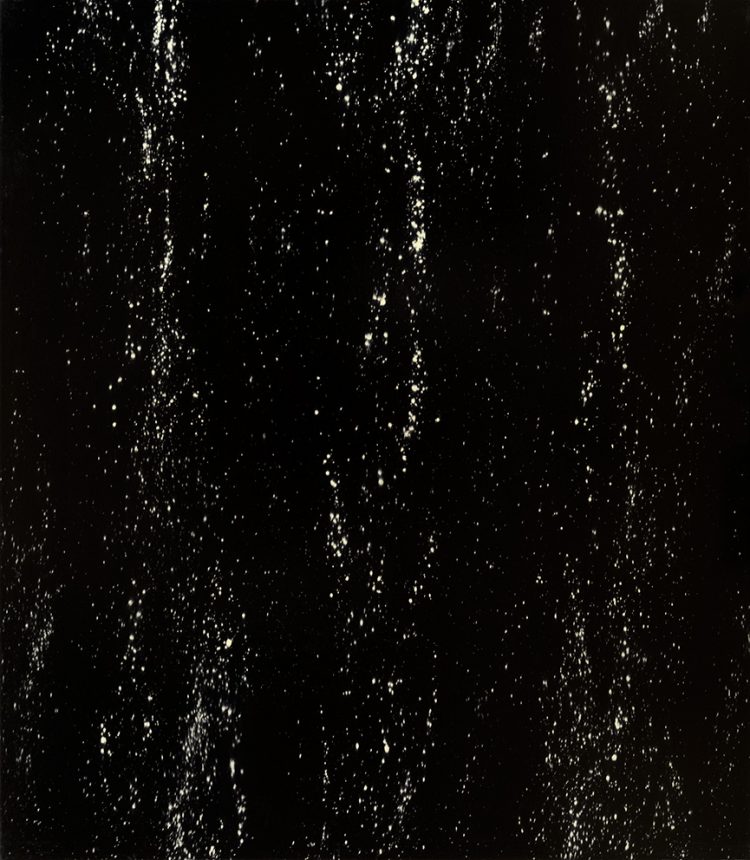

One must apply the same generosity of spirit and curiosity of the heart exuded by the wandering little prince to be able to engage with the monumental and often abstract paintings of Israeli artist Mosh Kashi. On his absurdly large, black canvas, a smattering of dotted white paint turns into a trail of meteors blasting through the sky in a faraway galaxy, where the night reigns eternal.

Mosh Kashi, Falling Lights, 2019

On a different canvas, just as dauntingly immense in proportion, the Tel Aviv-based artist plays with hues of white that clash with shades of light purple. The two colors melt into one another in the center of the large composition; only when the viewer steps away from the frame does it become clear that Kashi had successfully recreated the exact, ethereal light of dawn. Kashi explains that this work was the result of an attempt to depict “the moment when the light separates from darkness. That elusive moment when you can’t tell whether it’s night or day, morning or evening.”

Mosh Kashi, Blue Spectrum #2, 2019

For the painter, who has exhibited his work both locally and internationally, a keen interest in isolating everyday moments and immortalizing their essence on the canvas is the driving force behind such oeuvres. “I look for these moments and ask whether they can be captured through the medium of painting,” he says of the big, abstract paintings he exhibited in his most recent solo show, Crown.

“I want to paint something that will make you lose all sense of orientation. I want to make people enter a certain mental mode,” Kashi muses on the motivation that has guided him to shut himself up in his warm and large studio for the past three decades.

Looking for non-places with the inner compass

Indeed, the common theme recurring in most of the artist’s creations is a deliberate intangibility. Whether Kashi paints forlorn, nocturnal landscapes or solitary trees sprouting in dark and deserted fields, it is never entirely clear whether he is recreating a specific scenery. This vagueness, which has become an essential part of his visual language, has led critics in the past to refer to his paintings as symbolic representations of non-places.

Mosh Kashi, Ash Tree, 2019

“Often I felt that my artworks don’t portray a specific place. It could be any place. I would even say that they are timeless,” Kashi concurs as he welcomes me into his studio on a grey winter morning.

When I ask him why he is disinclined to explore specific spots in the real world, the artist pauses to reflect. “As much as we want to silence the biographical element of our lives, we can’t really cut ourselves off from it. For years, I didn’t want to make the connection between my biography and how my paintings looked,” he comments quietly – referring to the fact that he grew up with seven siblings and spent his teens in a boarding school. “Over time, I realized that a lot of things that I felt as a child found their way into my paintings. I always felt that I was creating my own world, since early childhood.”

The shadowy no man’s land that viewers are transported to in Kashi’s paintings reflects an “uncertainty of what will become of the painting,” he shares. “It’s like traveling overseas without a compass or a map and giving yourself up to the sensation of being lost. That moment moves me, because if I were creating from certainty I wouldn’t be doing it. The not-knowing opens such a big metaphorical space inside of me. It’s a place that is still phrasing itself.”

His one trusted ally, which appears in one way or another in every one of his paintings, is nature itself. But Kashi admits that he doesn’t draw inspiration from going outdoors, rather relying on his imagination and instincts. “For me, nature is like a huge dictionary that can contain so many things. Had I painted people, I would have had to perform an analysis that is almost dogmatic. But once I create something like this,” he says, pointing at numerous paintings leaning against the walls of the studio, “It’s a landscape but it isn’t. It’s a place but it’s a non-place. Nature provides us with a dimension that we can shrink, extend, stretch out in a way you can’t do with people. Nature is a possibility for an endless world.”

The momentum of a hand gesture

While the painter decidedly avoids painting people, many of the trees and shrubbery that star in his paintings have a distinctly human quality to them. Kashi creates tactile landscapes, where the breath of wind bending the tree sprigs is palpable and where the leaves’ veins jut out in silent sorrow.

“When I paint a landscape, it’s likely that I will charge it with an element of physicality. It’s not a conscious act,” Kashi admits. “You could look at my works and say that they revolve around nature and fauna; but nature for me is just a platform that transports me to a certain state of mind. You could say that the nature in my paintings is melancholic, but nature isn’t really melancholic. We project our feelings onto it.”

Kashi says that thoughts about the fragility of the body or his own physical presence accompany most of his works. As an example he shows me paintings from a series called “Ash Dreamer,” a meticulous body of work that consists of dozens of monochromatic paintings of enlarged leaves and other natural scenes. “I had made an encyclopedia of dozens of paintings, and wanted to create them using a material that I watered down so it would resemble ash. Think of botanists who craft textbook illustrations – it’s not what I did. The momentum of a hand gesture and of the brush, the mood of the painting… all of these create together a hidden, physical value,” he reflects.

Mosh Kashi, Ash Flora, 2016

When I remark that above all else, his artwork is highly aesthetic but not never too experimental, Kashi offers his own interpretation of beauty. “There is something about aesthetics that I connect to eloquence. It’s almost like how people speak; you hear people converse on the street or in the market, and there are different levels of language. I asked myself whether language was capable of carrying emotion. What if I go and make my language more precise? Our feelings are of the highest order, and if we explain them through a low dialect we create a big dissonance. That’s how I approach painting, I want to be eloquent through it.”

Before I turn to leave, Kashi invites me to stand in front of his ‘Falling Lights’ painting. “If you linger in front of it, then maybe you will slowly gain the recognition that you are standing in front of something you thought was monumental – a ray of stars stretching out far away – but suddenly it’s your size, ” he suggests.

As I leave his studio and proceed my walk down the street, I close my eyes for a minute and let his falling stars light my way. What Kashi had put into words every artist hopes to achieve – to make the divine tangible, within arm’s reach; to trace its outlines so a memory remains long after it is gone.

Discover & Collect Mosh Kashi’s works here.

Joy Bernard is a senior news editor at Israel’s leading English-language daily Haaretz. Based in Tel Aviv, she writes about politics, arts and culture in the Middle East for various publications.