I visited Shai Yehezkelli’s studio in an industrial area of south Tel Aviv on a mid-week evening, the streets were empty and so were the stairs I climbed to the top floor of the building. Yehezkelli is humble and pleasant, and it seems that he had built himself a world of his own, a little haven within the chaotic concrete monsters. We sat in the studio’s center, surrounded by his colorful, vibrant works. “I mainly paint,” he says when I ask him to describe his practice, “and sometimes I draw” he adds; “but to me these are two separate worlds that rarely collide.”

IS: Tell me about the process of making an artwork. SY: “I come to the studio every day and work on several pieces in parallel, with my attention given mainly to one or two paintings. At the same time, I create pallet paintings; these are papers, wood pallets, and pottery on which I apply paint leftovers until they become independently meaningful. The core characteristic of my work is jumping from one piece to another, juggling between universes and questions that I sometimes feel the need to step away from, only to be able to continue dealing with them in the future. It’s a process that may last two years or less than one day. Maybe it’s just ADHD.”

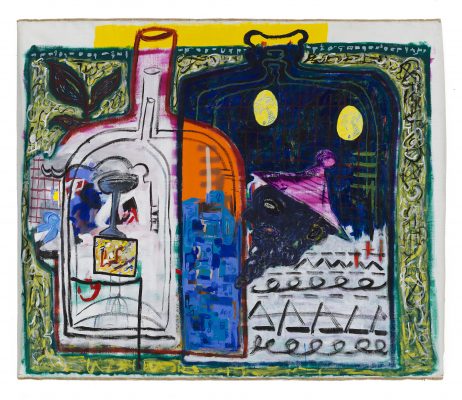

IS: And what inspires you in the process? SY: “There are no rules, no constancy.” He says determinedly. “Nearly a decade ago I changed my studio practice and stopped painting from observation or from photographs as I realized that what drives me to spend hours in the studio is not translating an object onto the surface. I favor facing the canvas “Tabula Rasa”, with no sketch or preliminary thought, but from a color gesture that leads me through the process, having a few subjects that I constantly go back to ever since I started painting. On one hand, these subjects are engraved perfectly in my head so there is no need for me to observe and on the other hand, I keep processing and changing them. There lies my challenge; I am more interested in experimenting and discovering what will come up, building something from scratch, and this method may often be frustrating. There are layers over layers of paint and erasures in many of my works, like reverse archaeology, I dig upwards to find something while I have no clue what I’m actually looking for.”

IS: But you can keep digging to infinity, so how do you know when the painting is complete?

SY: “I don’t. What I do have is that decisive moment to which I aspire but the ideas are being created while painting, investigating concepts like composition, color, and content. And the most important question, in my opinion, is which story do I choose to tell? The subjects of my work are issues that have always been of interest to me; identity, history, and culture of the place where I grew up; and my religious education with its ancient characteristics to which I can still connect today”.

Yehezkelli’s recent solo exhibition “Maarava”, was on view at Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami through last April. SY: “The exhibition focused on the ultimate contemporary definition of the West and my personal interpretation of the theme using the Wandering Jew, a recurring motif in my paintings since 2012” he explains, as I investigate how American viewers, of different backgrounds and cultures, understood and related to his work. “I find translating my paintings for an international audience very challenging. After discussing the works with local visitors, I understood that many of the elements I thought of as common knowledge, were actually very particular to the religious Jewish world. So in that sense, I didn’t find greater difficulty in the US than here in Israel. Concepts related to Israeli culture, on the other hand, required more explanation overseas.”

IS: Is this something you think of while creating an artwork?

SY: “No. In the earlier stages of my career, I debated on how explanatory art should be, and I came to the conclusion that it needn’t be. My catalogs, exhibition texts, and artist book are all accessible online so that viewers wishing to investigate my paintings and the ideas behind them can easily do so. In general, I believe there is no one right way to interpret a painting, and that art should not force its story on the viewers. Especially not my art and my story.”

This humble attitude Yehezkelli holds towards himself and his artistic path surprises me. He allows things to happen naturally, and it seems as if he accidentally got caught into the art world. SH: “I dropped out of high school and while my friends were enrolled in universities I was catching up on my finals” he admits. “Originally I wanted to study history and literature, but it required taking the SAT and I did not want to spend another year preparing. When a friend who went to Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design recommended it, I simply looked for the most general subject I could study there, genuinely thinking that art school graduates don’t necessarily become artists. I finally got in and things just happened, but I was facing a challenging process of first getting to know that art world, and then exploring it and myself within it.”

Examining his paintings throughout the years, one can point out a certain change in Yehezkelli’s style sometime around 2014. SY: “Something changed when I started teaching art” he agrees, and explains, “prior to teaching, my perception of art was somewhat tainted with cynicism. I was suspicious and avoided being obsequious. Given my religious education background, I was unfamiliar with other artists and did not grasp art as sublime. Then I arrived at Bezalel and discovered modern and contemporary art, noticing how the rituals that revolve it assume a religious halo; the silence that prevails in galleries and museums, the prohibition of touching works of art, the spiritual conversations and transcendent thoughts behind it. I was intellectually and sensually intrigued by all these but felt the gap between my own perception of spirituality and the artistic experience; regarding beautiful pieces that do not provide a religious substitute. I did not want to “trick the viewers” and expect them to worship my art, but I quickly realized that by simply hanging a painting on the wall, it becomes supreme. When I started teaching, witnessing how art affects people, I lost a great deal of my suspicion and gave in to using all means of artmaking, enriching my paintings without feeling guilty or judgmental. I still struggle with maneuvering the concepts of depth and perspective though.”

Yehezkelli is very self-aware but at the same time, he seems to have built himself an isolated world of his own, one that I try to understand through the subjects he reuses over and over again in his paintings, most of them being masculine figures. SY: “I usually paint self-portraits,” he says, “not necessarily physical, but conceptual self-portraits. I don’t feel it’s adequate for me to paint a female figure, since representing one also means speaking her voice out. Just as I won’t paint other people, instead, I isolate the characteristics of these subjects, suiting them to my alter ego. So my paintings are not representations of men’s world, but my world.”

The Wandering Jew is one of these recurring motifs in his paintings. “It started from a book I read that encouraged me to further investigate the Christian myth of the Wandering Jew. I wanted to paint a figurative image of the character from a personal point of view, from my own experience of detachment from the physical place in which I live. I obviously have my space and the people I love here, but generally, and in recent years specifically, I have mixed feelings regarding Israel, it just doesn’t feel mine. On the other hand, I have never lived abroad and have never felt at home in any other country I visited. This duality relates to the myth of an individual who is cursed to run away from one place to another, never knowing solid ground beneath their feet, a home. These are clearly not solely Jewish people; it happens today with refugees around the world, and I am sure there are some Swedish people who feel the same.” IS: So where is home? I try to conclude. SY: “I don’t know where my home is, or how to define it. Is home the place where I grew up? A place in which I feel comfortable? Somewhere that relates to my sentimental heritage?”

We say goodbye and I leave the studio wondering about this question as I walk towards “home”.