In one of his latest paintings, created over the past year, Israeli artist Shai Yehezkelli depicted an orange row boat gliding along magenta-hued waters. Passengers don’t occupy Yehezkelli’s waterborne vehicle. The eerie absence of people is exacerbated in this frame by the addition of three oars that seem to dangle unnaturally from within the ship’s interior, with no human hands to clasp and move them.

Shai Yehezkelli, Ship of Depression, 2020

Shai Yehezkelli, Ship of Depression, 2020

A closer look at the scene, which bears the strong color scheme and flat pictorial plane that have become identifiable with Yehezkelli’s oeuvre, enhances the feeling of unease. A small, round and dark hole mysteriously protrudes in the water, at once appearing out of place but also indicating that the entire essence of the painting might get sucked into this cavity until the canvas is hollowed out. Thus, the most innocently unremarkable visual narrative of a nautical journey turns in Yehezkelli’s hands into a potential representation of doom.

It is often said that the brushstrokes of a painter and his or her choice of colors or themes are the factors that determine what their work will appear like and give it its aesthetic values. But with Yehezkelli, who has showcased his craft in numerous exhibitions both in Israel and abroad, it appears that the art’s defining quality is the uncertainty it stirs in the viewer who observes it. Small and seemingly suddenly executed decisions to add or reduce color or shape, layers of paint that conceal initial attempts, ominous signs and surrealistic symbols all compose an inner grammar – which dictates how the painter’s work should be read.

Shai Yehezkelli, Esoteric Painting with Signature, 2020

Shai Yehezkelli, Esoteric Painting with Signature, 2020

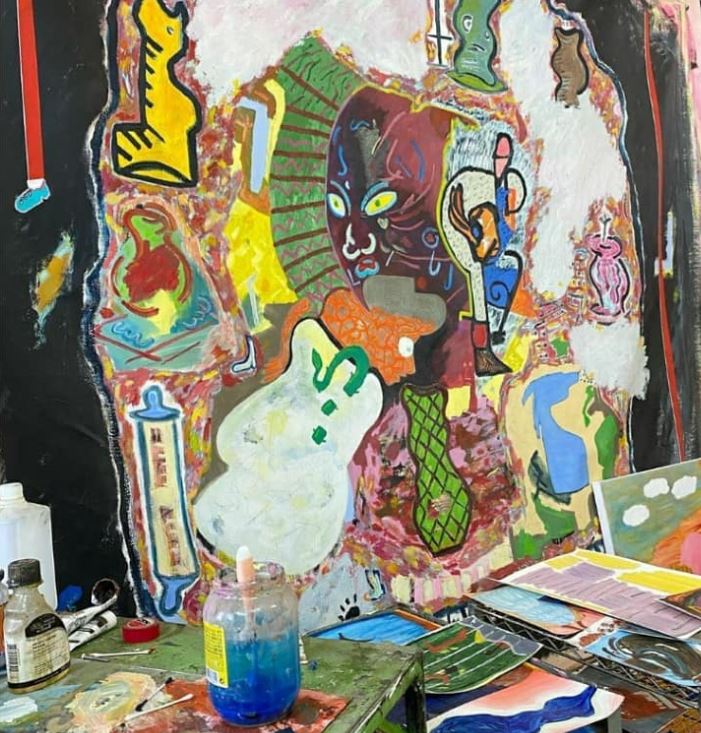

On a recent visit to his studio, which is situated in the heart of a south Tel Aviv neighborhood that has become the hub of the contemporary art scene, Yehezkelli acknowledges that his creative path is fraught with surprises and even mistakes. “Surprising myself is definitely a key word when it comes to considering my process,” he tells me. “It’s complicated, because when I teach art students, I do instruct them to follow the preparation stages that are crucial to beginning painters, such as making a sketch or working with a photographic reference. So I see the educational value in that, but for my own work these premeditated gestures hold no value.”

What is it that he does seek but cannot envision in advance? “The real value is to know where I want to arrive at through my painting, and simultaneously to have no clue at all. The not-knowing and the lack of control are what motivates me the most.”

No illusions

Painting progressed in a historical trajectory from indoctrinative in the Middle Ages to mimetic in the high glory days of the Renaissance, and finally existed for its own sake at the outset of the current wave of postmodernism. Yehezkelli, a painter who likes to discuss and carefully consider past traditions, is reluctant to let his paintings be placed somewhere along these various definitions. He adamantly objects to the notion that paintings should be a window to the world or possess illusory qualities, thereby creating works that refuse to appear three-dimensional. But he also continuously hopes to surprise himself and opts for new shades, subjects and forms that he hasn’t tested before.

Soft spoken and carefully weighing his words, the Bezalel-educated artist’s glance flits between me and the rows of paintings that hang on the walls of his studio. “I don’t think about painting as something that needs to retain an illusion. A painting also doesn’t need to show, or rather emulate, reality,” he asserts decidedly.

Yehezkelli explains that he prefers “a painting that is flat, so that the viewer looking at it isn’t provoked to ask whether someone carried out a deceptive move. It stems from a feeling of unease about art that attempts to create an illusion, because I think that this is an unimportant motivation. But on the other hand, at one point I understood that this is somewhat of a lost cause, because as soon as you place one layer of color next to another, you’re already creating an illusion.”

This objection to creating a deceptive facade manifests itself in different elements that recur in his paintings. The net-like, intersecting lines of the painting grid often make their presence known in his paintings, emerging like telltale signs which indicate that their maker carries out an ongoing dialogue with himself about the purpose of art-making.

Another example of Yehezkelli’s tendency to raise questions about the meaning of the medium is his treatment of human figures. Almost all of the characters in his works are male faces in profile, many of which he defines as self-portraits. The people in Yehezkelli’s paintings sport unusually elongated features and impossibly thin or unrealistic bodies, which lend them a cartoonish air.

Shai Yehezkelli, Border Painting, 2020

Shai Yehezkelli, Border Painting, 2020

Works like Border Painting, a painting that depicts two obscure characters in profile against a stark, blue backdrop and zig-zagging yellow lines, embody his fascination with these motifs. The artist clarifies that the moves that I detect in this painting and others are not necessarily carried out defiantly. “I’m in a constant struggle with the medium and with the painting process,” he admits. “Then the paradox is that I struggle with my own struggle. I’m not an adventure-seeking person, I always look for a safe space. If I could, I would literally not leave my house or the studio for days. But in my work, I look for the exact opposite – I want the ground to fall out from underneath my feet.”

Between falling and levitating

The desire to push himself to new limits in order to lose his sense of equilibrium leads Yehezkelli to place the figures in his paintings in liminal spaces. A constant in his work is the image of a man walking or hovering within the painting, captured on the canvas in mid-step in a gesture reminiscent of Futuristic paintings that sought to express, above all, live movement.

“I think my interest in the figure that is in the process of running or walking came from an idea I had about a character, which I understood that I had kept returning to in my work, especially in the past five years. I have been trying for some time now to understand who is this character that I keep painting,” he muses.

“On the one hand,” Yehezkelli suggests, “it’s an analogy for painting. When you look at a figure that is about to leave the frame, it hints at the notion that the painting is about to be emptied of the substance occupying it. It’s also a reminder that the canvas was blank at one point. On the other hand, it represents thoughts I have about not wanting to stay stuck in one place or get too static. That’s important for me as a painter.”

Yehezkelli ponders a painting leaning against a wall behind us, where a long-limbed figure looks like it could be marching towards the viewer or just as well turning away. “Look, in the majority of these paintings, the runner or walker doesn’t have a ground underneath him, or his legs don’t touch the ground. I think it reflects the feeling that you don’t have a ground to stand on. Maybe it’s a bit like the sensation we all know from sleep, when we dream about falling. It’s a state that disturbs and preoccupies me. It’s something I feel most of the time.”

Shai Yehezkelli, Runner (Selp Portrait), 2020

Shai Yehezkelli, Runner (Selp Portrait), 2020

So are his runners falling or levitating? “A little bit of both,” he responds with a smile.

A tragic comedy

Yehezkelli is unafraid to correspond in his works with art history. Some of them reference artistic styles, like Boy with Red Shirt, a fragmented and colorful portrayal of a figure that echoes the Cubist predilection for breaking down the multiple components of a picture. Others are direct nods to iconic artworks, like Angelus Novus (2), in which the painter offers his own modern interpretation for a canonic piece by the German-Swiss painter Paul Klee.

Shai Yehezkelli, Angelus Novus (2), 2020

The original work from 1920 depicted a disturbing-looking angel. In Yehezkelli’s version, the emphasis is on the distorted face of the creature, which looks like it is composed of doors that could open up to a world tucked within the densely-colored surface. Klee’s work has become renowned after it was analyzed by German philosopher Walter Benjamin. The latter wrote that Klee’s figure represented the angel of history, warning against the bad tidings of the future. “But a storm is blowing from Paradise,” the critic had written, a sentiment that permeates Yehezkelli’s painting and one he acknowledges can be detected in many of the moody landscapes and portraits he created in recent years.

As we discuss the renowned artwork and the essay that helped it gain acclaim, he reflects on his current motivation to paint. “In Benjamin’s text, he addressed some kind of double glance, a moment of looking back and forth in time that brings a sense of terror. It is exactly what I’m interested in, this figure that can see a pending disaster. As an artist, all you can do facing this disaster is to illustrate it. I guess that you could say that there is an atmosphere in my newest paintings of a toxic environment, or something that came right after a catastrophe transpired.”

While some of his latest works do invoke a sense of gloom, Yehezkelli believes that at the heart of his practice is the choice to view the world through an amused perspective. “I see painting as my playing field. Even a painting that has a tragic core to it needs to have some element of humor in it, something that’s a little bit tongue-in-cheek. At the end of the day, painting is magic. Sometimes it’s a very complex magic, and sometimes it’s just a small trick.”

Discover & Collect Shai Yehezkelli’s works here

Joy Bernard is a senior news editor at Israel’s leading English-language daily Haaretz. Based in Tel Aviv, she writes about politics, arts and culture in the Middle East for various publications.